This article was contributed by Dr Frederick Cowell from the Birkbeck School of Law’s Department of Law.

The High Court today handed down their judgment in the case brought by Gina Miller and Deir Dos Santos against the Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union.

Billed as the ‘Brexit’ litigation, what was at issue was whether the Prime Minister had to go to parliament before triggering Article 50 of the Treaty of the European Union (also known as the Lisbon Treaty), which would set in motion Britain’s exit from the European Union. The judgment was first and foremost a question of resolving a basic legal question; is it the government or parliament that has the power in these matters?

The court were, in fact, keen to cut out the party political question altogether, declaring that they were “dealing with a pure question of law”. The judgment is, however, likely to become the ultimate political football and within half an hour the Government had announced that intended to appeal the decision to the Supreme Court on the 7th of December.

The core issue was the scope of prerogative powers relating to foreign policy, which are held by the Prime Minister and other government ministers. Historically, treaties were signed between monarchs by their representatives and, as the UK’s constitution became more democratic in the nineteenth century, prerogative powers were delegated to government ministers.

Many prerogative powers are now governed by legislation – for example, the 2010 Constitutional Reform and Governance Act put the power to manage the Civil Service onto statute governed by clearly definable legal powers. Prerogative powers are not easy to control as they can be exercised by ministers without the approval of parliament – for example Margaret Thatcher’s decision to ban trade unions from GCHQ (the secret service signal intelligence headquarters) did not require an Act of Parliament in the way that her other restrictions on trade unions did. They are also difficult to control through the courts, which are often reluctant to intervene in areas where these powers are exercised, especially when it comes to foreign policy. On the eve of the Iraq war the High Court held that they could not hear a case from the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, who were asking for Tony Blair to seek a resolution from the UN Security Council authorising the use of force.

Shortly after becoming Prime Minister, Theresa May took the position that she didn’t need parliament’s approval to activate Article 50 and she could exercise her prerogative powers to take the UK out of the EU. In fact, she went so far as to guarantee in October that Article 50 would be activated by the end of March. In 1971 the question of whether the government should accede to the European Economic Community (as it then was called) was debated in the House of Commons, even though technically, under the UK’s constitutional system, the Prime Minister of the day Edward Heath did not need an Act of Parliament to accede to the EEC.

What he did need parliament’s approval for, and what was at the heart of the Brexit litigation, was the 1972 European Communities Act which brought EEC law (later EU law) into UK law. This took nearly 300 hours of debate to pass, with Labour and Conservative MPs voting against their own party line repeatedly in an early indication of how divided the two main political parties were on this issue.

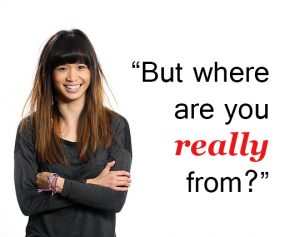

The 1972 Act – as the High Court Judgment noted – created rights for individuals as well as empowering the lawmaking institutions of the EU (paragraph 37 R(on application of Miller) v Secretary of State of Exiting the European Union). There were three kinds of right created under the 1972 Act; rights the EU had created and could be incorporated into UK law (such as the 48 hour working week and the right to cheap data roaming), rights enjoyed by citizens of other EU member states in the UK (the right to work) and rights enjoyed by UK citizens in other EU member states (the right live in other EU states).

The big issue was whether the loss of rights conferred by the 1972 Act could not sanctioned by the Government acting without parliamentary authority. The Court noted that the lawyers for the Secretary of State had effectively conceded that some rights would be lost were this to happen (para 63). Therefore, the question was who should make the decision. In deciding this, the High Court noted that since the English Civil War in the seventeenth century the basic proposition was that the Crown (the executive branch of government) could not override parliament.

It is noteworthy that when the courts have previously reined-in abuse of ministerial power they have pointed out that one of the founding principles of Britain’s unwritten constitution was parliament’s supremacy over the executive. The Secretary of State’s lawyers relied heavily on an earlier court ruling at the time of Maastricht Treaty in the early 1990s which held that ratifying a new treaty was within the government’s prerogative powers. But this was a different question all together as Paragraph 94 of the judgment made clear, as the government’s actions on an “international plane” (i.e. activating Article 50) would remove rights granted via a domestic statute (the 1972 Act): therefore they needed the approval of parliament.

What this means is difficult to say at this point, although the Government’s strategy – and possibly its timetable for leaving the EU – have been dealt a significant blow. Whilst there are potentially points of law to appeal in the judgment, it is difficult to see some of the core conclusions reached by the High Court being overturned by the Supreme Court as they follow a century of established case law on the subject.

The real danger for the Government is that it will be very difficult to get their version of Brexit in a statute through both the House of Commons and the Lords, as Jolyon Maugham QC explains here. This is why political commentators are speculating heavily on the possibility of an election next year which would give the government the political mandate, and the Commons majority to push exit legislation through the House of Commons. Although the status of the June 23rd referendum was only advisory, were a Government to be elected in a General Election on a pro-Brexit manifesto there would be no way of stopping that in parliament.

In his

In his

Many readers will welcome the

Many readers will welcome the