Dr. Olivia Sheringham from Birkbeck’s School of Social Sciences, and PhD researcher Rebekka Hölzle reflect on a creative workshop at Birkbeck exploring care as concept, method, and practice in the context of migration and solidarity.

(Why) should we be thinking about care in the contemporary moment?

What is care, what are its limits?

What are the relationships between care and creativity; between care and power?

Living in times of a grave neglect and denial of care for many communities and spaces across the world, it might not be surprising that ‘care’ has become an often-discussed buzzword within academia and beyond. Care seems to be everywhere, but where does it begin and end? And does this omnipresence mean it is no longer a useful concept? Should we still be thinking about care – and if so, why?

These are some of the many questions that we explored over the course of a half-day creative workshop at Birkbeck University. Our incentive to co-host the workshop was to share with others some of the insights and dilemmas we’ve experienced in our own research engagements with care in the context of the UK’s hostile environment. Rebekka’s PhD examines the every-day survival and resistance practices of migrant women with ‘no recourse to public funds’ in London, whilst Olivia’s British Academy/Wolfson funded fellowship project explores networks of care and solidarity with refugees and people seeking asylum in London. In different ways, we’ve been grappling with the possibilities and limitations of care as a framework for engaging with – and enhancing understandings of – marginalised migrants’ everyday practices of survival and resistance.

Through the workshop, we wanted to open up a space of exchange and dialogue with other researchers and practitioners, to creatively, critically and care-fully explore ‘care’ as theme, method and ethics. The participants included PhD students, creative practitioners and researchers from other London universities. Inspired by Rebekka and Clau di Gianfrancesco’s ‘collaborative knowledge production’ workshops, we aimed to hold a creative and caring space with a flexible structure, offering shared materials, questions, and prompts, to think with care together. As we’ve experienced through our own research, care can mean many different things to different people, care is contextual and contingent, care can relate to practice, labour, ethics, affects, and relations. Having both spent a lot of time in recent months reading academic literature around care, we wanted to explore how we could bring some of this work into the space of the workshop without producing a sense of hierarchy between this published knowledge and the embodied, spontaneous, emergent knowledge produced during the workshop and that participants brought into the space.

In both of our research projects, we have been experimenting with creative and participatory approaches, moving away from top-down defined ‘research outputs’ and instead remain open to a collaborative creative process. Throughout the workshop we took a similar stance, starting with games and creative activities that drew on techniques from the ‘Theatre of the Oppressed’ to initiate processes of embodied learning and dialogue. This included creating a collective care statue, for which, without thinking too much, participants were invited to hold a pose they associated with care – an activity that Olivia had previously done in different workshops and research contexts. Without words, these gestures already revealed the multiple meanings of care: as personal and collective, as protection and connection, as rest and repair, as involving human and more-than-human. We also played the Theatre of the Oppressed game, Colombian Hypnosis, where people workin pairs and take it in turns to lead the other person around the space using their hand as a guide. This game invited a discussion around the relationship – and fine line – between care and power, and some reflections on the ‘burden’ of responsibility for those taking the lead, those ‘taking care’, and a potential sense of relief to be led.

We then spent some time sharing our research – drawing attention to our understandings of care as both object of study and method. Olivia talked about some of the ambiguities around the notion of ‘radical care’, and the trouble we both found with seeming oppositions in the literature between, for example, institutional versus radical care, charity versus solidarity, or a tendency to romanticise care as survival. Rebekka reflected on engaging care as method, and our shared commitment to ‘care-full’ methodologies as radical ethical practice. In the context of the absence of care within a racist, violent migration and border regime, care can become a fundamental mode through which to resist the hostile environments produced by the British state. We also reflected on the challenges and limitations of this commitment to care-full methodologies, and the risk of reproducing the same power imbalances that the research is seeking to disrupt.

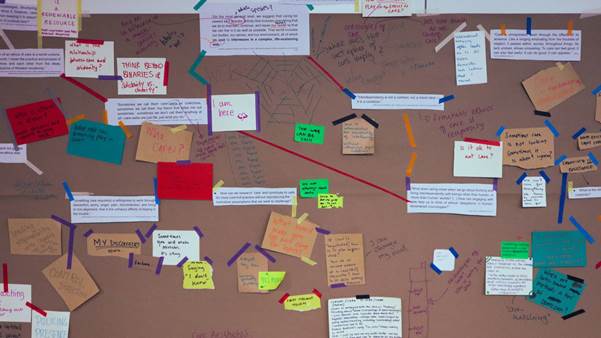

Our conversation prompted a collective reflection on the indefinability of care, of care as necessarily involving reflection and negotiation. In the next activity, we sought to visualise this through a collective collage in which all participants had time to engage with quotations and words on the wall through writing, drawing, and using tape to create connections between what was already there, as well as each other’s additions. This collective crafting enabled us to exchange and connect knowledges, ideas, and questions around care, while staying with its messiness.

We ended the workshop with a set of individual and collective poetry writing activities, reflecting on what ‘care is not’– what needs to be refused for care to flourish and second, sensory poems imagining what a ‘pocket of care’ would look/smell/feel/sound like. In a similar way to using our bodies to engage and produce new knowledges during the theatre and crafting activities, these exercises opened our imaginations to expand the lexical boundaries of care, and its absence.

In the words of one participant’s poem: ‘Care is labour, is slow it is messy and, in its complexity, it strives to oppose commonsensical definitions of it. But this does not mean that care is understood with jargon-full academic ruminations.’ We hope that the workshop created a space to think with care beyond academic jargon, to embody care and to practice collective care within the space. To stay with the trouble and the messiness of care, to recognise its limits and contradictions – but also to imagine the care that could be, the ‘might be’ and the ‘not yet’.

“Care is movement – where is it going?

Sometimes it’s going nowhere

Sometimes it is returning”

All photos credited to Rebekka Mirjam Hölzle

More Information:

- This post is also available on www.rebekka-hoelzle.org

- Contact Olivia

- Contact Rebekka